A Shepard of Meteorites & Minerals

Museum collections don’t hold their physical or intellectual value purely with the specimens themselves. Collections, of any sort, can reveal a wealth of information about both their own personal histories and the histories of the collector. Why were they collected? Who collected them? When were they collected, and what made them valuable? At McKissick Museum, our historic natural science collections are no different. Within this material, much of our focus is based around Thomas Cooper, the esteemed University of South Carolina president and the source of our collection. However, pieces of our historic collection also bear the mark of other great men, including Charles Upham Shepard.

Although Charles U. Shepard has no distinctive connection to the University of South Carolina, he did make a significant contribution to the collection. In 1853, Dr. Richard Brumby, a Chemistry professor at what was then South Carolina College, purchased a number of minerals and meteorites from Dr. Shepard, who at the time was well known as one of America’s first distinguished mineralogists. A Rhode Island native, Charles U. Shepard spent a year studying at Brown University before transferring to Amherst College in Massachusetts. Upon graduation in 1824, Shepard spent a year studying and offering private chemistry lessons in Boston, until he joined the faculty at Yale in 1827. In 1833 Shepard moved to Charleston to teach at the South Carolina Medical College, where he remained until 1870. During his time in Charleston, Shepard discovered the value of South Carolina phosphate deposits. In his later years, Shepard divided his time teaching both at his alma matter Amherst College, and SC Medical College in Charleston. He died in Charleston in 1886.

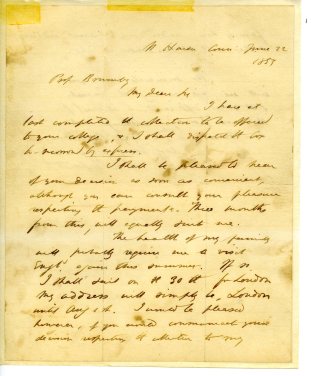

During Shepard’s time in South Carolina, it is feasible that he crossed paths with Professor Richard Brumby. Although we are unsure of the relationship between the two, we do know of communications and the transaction between Shepard and Brumby, through two well preserved documents. Over the past few weeks the team here has been hard at work transcribing the contents of a letter Shepard penned to Brumby, and a list of specimens intended for sale. In case reading 161 year old script isn’t your thing, the letter reads:

N. Haven, Conn June 22

1853

Prof. Brumby

My Dear Sir,

I have at last completed the collection to be offered to your college, and I shall dispatch the box to-morrow by express.

I shall be pleased to hear of your decision as soon as convenient, although you can consult your pleasure respecting payment. Three months from this, will equally suit me. The health of my family will probably require me to visit Engl’d again this summer. If so, I shall sail on the 30th for London. My address will simply be, London until Aug 7th. I would be pleased however, if you could communicate your decision respecting the collection to my family here under my present address; + they will let me know in Engl’d.

The minerals sent, you will see, are among the rarest and most difficult to obtain (for the most part), although not handsome, or ∧often in large specimens.

Very truly & respectfully yours,

C U Shepard

Shepard’s offering consisted of 99 specimens, and he noted that “the meteorites are chosen so as to illustrate as far as possible all the leading varieties among these bodies… The collection if taken, will make the Columbia cabinet the 2nd in point of numbers and variety in the U. States, in possession of any college. The Yale is the first.” Of the original 99 specimens, McKissick is still in possession of 72 specimens. Part of the mission of our current IMLS grant work is to identify these historic specimens, and ensure that they are properly cataloged and documented. However, some specimens were lost in the midst of the Civil War, some were transferred to other institutions, and yet others simply misplaced in the bustle of the past 161 years, making our job easier said than done.

In 1877 Shepard sold the majority of his personal collection (more than 25,000 specimens!) to Amherst College, though it was destroyed in a fire in 1882. He immediately began collecting again and, after his death, his son donated the collection in part to the Smithsonian, and again to Amherst College. To see some of Shepard’s minerals, his letter (and crafty penmanship) for yourself, be sure to stop by the third floor of McKissick Museum and check out the Natural Curiosities gallery!

by Alyssa Constad

Curatorial Assistant

The Institute of Museum and Library Services is the primary source of federal support for the nation’s 123,000 libraries and 17,500 museums. The Institute’s mission is to create strong libraries and museums that connect people to information and ideas.